Introduction

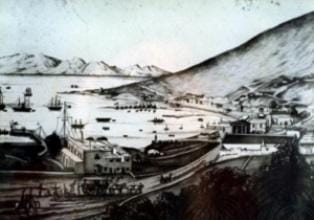

Reaching back to around 1650, Simon’s Town boasts a wealth of historic and strategic interests. It has been a naval base and harbour for more than two centuries and is home to beautifully preserved buildings, a colourful military past, and a rich and culturally diverse heritage.

The part which Simon’s Town has played in maritime strategy is inseparable from that of the Cape of Good Hope and South Africa as a whole. The meeting point of the two great oceans, the Atlantic and the Indian, is a key focal point of maritime trade between East and West. Inevitably, it followed that the two good anchorages – Table Bay and Simon’s Bay – became important havens for shipping. The dangers of the Table Bay anchorage during the winter months were quickly and forcibly brought to the notice of seafarers but were tolerated when the callers were few. As ships began to frequent Table Bay in increasing numbers at all seasons of the year, the incidence of shipwrecks during the winter became greater than could be borne with equanimity.